Manhattan Project research at Purdue propelled Chemistry Department's postwar growth

2023-07-07

Writer(s): Steve Scherer

The upcoming release (July 21) of the biopic Oppenheimer has renewed interest in the history of the Manhattan Project - the classified United States nuclear weapons program led by physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, the first director of the Los Alamos Laboratory.

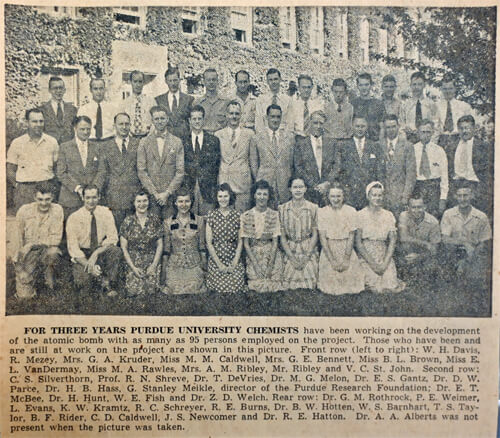

The project involved nearly 130,000 people, where research and production took place at more than 30 sites across the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada. At Purdue, more than 100 people were secretly working on the endeavor during the 1940s.

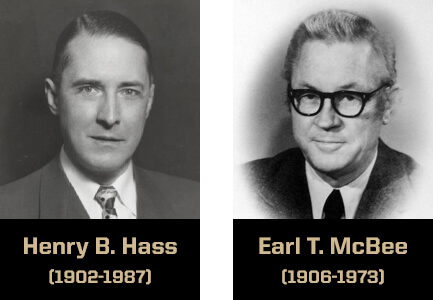

Professors Henry B. Hass and Earl T. McBee led Purdue Chemistry’s Manhattan Project research that began in 1942. Hass was department head during the war years. McBee earned a Ph.D. in 1936 as a member of Hass' research group, and joined the faculty that same year.

"McBee was relieved of his teaching duties in 1943 to spend full time in directing the research work connected with the development of the atomic bomb," the university revealed in a press release printed by the Purdue Exponent on August 11, 1945 (PDF).

According to McBee, his lab initially had two graduate students supported by the Manhattan Project, where they were "developing fluorinated compounds desired for the separation of uranium isotopes."

Learn more about Fluorine Chemistry research at Purdue during the Manhattan Project

“Harold C. Urey, who was in charge of the Manhattan Project at Columbia University, is the one who invited me to participate and to take some of the money. This later resulted in a substantial grant in which I had about 70 people - faculty and graduate students - working on fluorine chemistry. We became quite involved in the Manhattan Project,” McBee recalled in a 1970 Purdue University Office of Publications Oral History interview.

Dr. McBee sought the answer to a cooling agent which could be used in handling the radioactive material. Without such an agent, the atomic bomb project would falter and fail.

Other schools were working on the same problem, but substantially it was the agent developed on the West Lafayette campus which was adopted. Later Purdue researchers discovered a much more inexpensive coolant.

With one assignment completed, Dr. McBee and his staff were called upon to solve another baffling complication.

Uranium, the ore from which plutonium is extracted for the bomb, can be used over and over again. Only a small portion is debilitated at a time.

At Oak Ridge, Tenn., a recovery plant was in operation but was not working as effectively as desired. Increasing the recovering efficiency was the Purdue project.

Under Dr. McBee’s direction the only pilot plant in the nation was set up. With it, the scientists discovered the proper method to recover the precious ore.

"Hoosier Atom Smashers" - December 12, 1948, feature article in The Indianapolis Times, Earl T. McBee papers, MSF 538, Box 1, Purdue University Archives and Special Collections, Purdue University Libraries.

“They [scientists at Oak Ridge] were having a lot of trouble in recovering by-products of uranium. They wanted me to move my research team and send the people to Oak Ridge, and I advised them that I thought most of my team wouldn’t move. It would be a mistake,” said McBee, who served on the top governing boards of the Manhattan Project.

“So, we changed our research program from organic chemistry to inorganic chemistry and set up, I guess, what might be the third and last pilot plant on the Purdue campus, in which we developed processes for the separation of and recovery of uranium. This was all done for the Manhattan Project,” McBee said.

According to the Purdue Reamer Club, the obsolete Purdue Locomotive Test Facility building (once located near present-day Brown and Potter buildings) was given to the Department of Chemistry as extra lab space.

"In all, counting graduates, service staff, and members of the permanent staff, more than 100 persons were employed on the project, with a budget of more than $700,000," McBee published in a 1946 declassified scientific article, Fluorination and Atomic Energy.

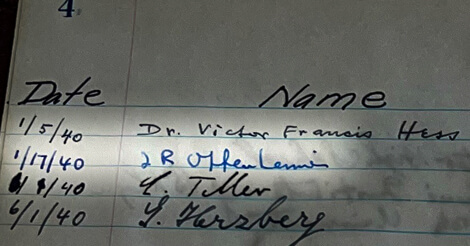

Purdue Chemistry Manhattan Project Members, 1945 - Earl T. McBee papers, MSF 538, Box 1, Purdue University Archives and Special Collections, Purdue University Libraries. Click on image to enlarge.

McBee said the Manhattan Project stabilized the department during WWII, and the research investments on campus propelled Purdue Chemistry's growth during the postwar.

“We had one of the largest graduate teams in chemistry during the war, and it was because of this contract involving about 70 people that we were able to get many of the students deferred to carry on their research. So, at the end of the war, we had a strong-going graduate research program, and many schools didn’t have this,” McBee recalled.

“Following the war there was quite an influx of GIs with grants for graduate teaching assistantships so that we tended to grow and grow, and grow pretty rapidly at this time,” said McBee, who served as chemistry department head from 1949-1967.

Read about Purdue Chemistry Professor Robert Benkeser’s encounter with an atomic spy.

Purdue Physics and the Manhattan Project

Chemists were not the only Purdue scientists working on atomic research. Led by Professor Karl Lark-Horovitz, the Purdue Physics Department was doing pre-war work in nuclear physics as early as 1935.

In 1940, (three years before supervising the Los Alamos Laboratory) UC Berkeley physics professor J. Robert Oppenheimer delivered a series of ten lectures at Purdue on "The Crisis in Modern Field Theory,” according to Department of Physics and Astronomy records.

According to the Atomic Heritage Foundation, "The physicists at Purdue operated the university’s cyclotron to determine cross sections for several molecules, which would prove key to developing the hydrogen bomb."

At some point in late fall of 1943, nearly two-thirds of the [physics] faculty and graduate students engaged in nuclear research at Purdue, simply vanished from the campus all leaving behind the same post office box as a forwarding address. The locals, of course, had no idea where they went, but assumed naturally that it was somehow related to the war effort. Only much later did they discover that Los Alamos, New Mexico, had been their destination.

Notable Purdue Physicists who worked at Los Alamos:

-

Marshall Holloway directed the secret Manhattan Project cyclotron assignment at Purdue. At Los Alamos, he worked on the Water Boiler, an aqueous homogeneous reactor. Holloway studied various safety aspects of the Little Boy bomb and helped assemble the plutonium pit for the Trinity test.

-

L. D. Percival King was an instructor on the Purdue cyclotron team. He and his wife, Edith, worked at Los Alamos on the project. Both observed the Trinity Test, standing next to 1938 Nobel Prize winner Enrico Fermi.

-

Raemer E. Schreiber (Ph.D. 1941) worked on the Water Boiler at Los Alamos. He was part of the pit assembly team for the Trinity test, and later helped assemble the weapon on Tinian Island.

-

Harry Daghlian (B.S. 1942) accidentally irradiated himself on August 21, 1945, during a critical mass experiment at the remote Omega Site of the Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico. He died 25 days later from radiation poisoning.

Declassified Document

This declassified April 5, 1943 letter (PDF) from Robert Oppenheimer to James B. Conant, Chairman of the National Defense Committee, informs him about the proposed timetable for Purdue physicists being sent to Los Alamos.

Did You Know?

During Manhattan Project research, physicists at Purdue needed a secretive name for a unit with which to quantify the cross-sectional area presented by the typical nucleus and decided on "barn." According to legend, the term was coined by physicists Marshall Holloway and Richard Baker while they were dining at the Purdue Memorial Union. The two physicists described the constant "for nuclear purposes was really as big as a barn."1 Today, the Barn unit is used universally in nuclear and high energy particle physics.