Helium first discovered during 1868 eclipse; the element later developed by 20th century chemist, Purdue science leader

2024-03-27

Writer(s): Steve Scherer

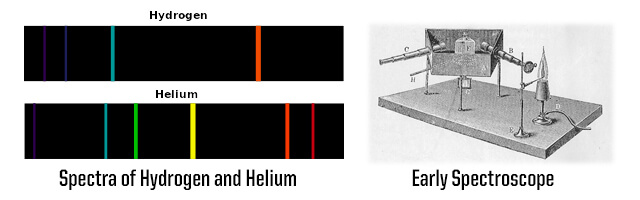

The chemical element helium was first observed during an 1868 solar eclipse in India. French astronomer Pierre Janssen focused a spectroscope on the solar prominence where he noticed a new, bright yellow line in the spectrum of the sun’s chromosphere.

Two days later, English astronomer Joseph Norman Lockyer independently observed the emission spectrum of the chromosphere which included the same yellow line.

Several years later, Lockyer and the English chemist Edward Frankland determined that the new line was an element in the Sun not previously discovered on Earth. They suggested naming the new element “Helium” from the Greek word for Sun “Helios.”

This was the first time a chemical element was discovered on an extraterrestrial body before being found on the Earth.

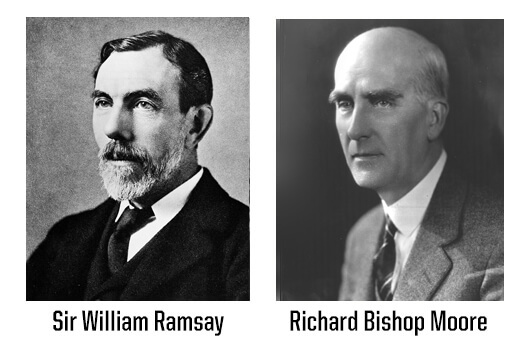

Nearly thirty years later in 1895, Scottish chemist Sir William Ramsay was the first to isolate terrestrial helium from cleveite, a uranium mineral. He was awarded the 1904 Nobel Prize in Chemistry "in recognition of his services in the discovery of the inert gaseous elements in air" – with discoveries such as argon, helium, neon, krypton, and xenon, leading to the creation of the noble gas group of the periodic table.

In 1907, a 35-year-old University of Missouri scientist, Richard Bishop Moore, spent a sabbatical year working with Ramsay in Scotland. This experience laid the foundation for Moore’s later research in the development of the radioactive ores in Southwestern Colorado and Eastern Utah and helium extraction as lead scientist for the U.S. Bureau of Soils and later the Bureau of Mines.

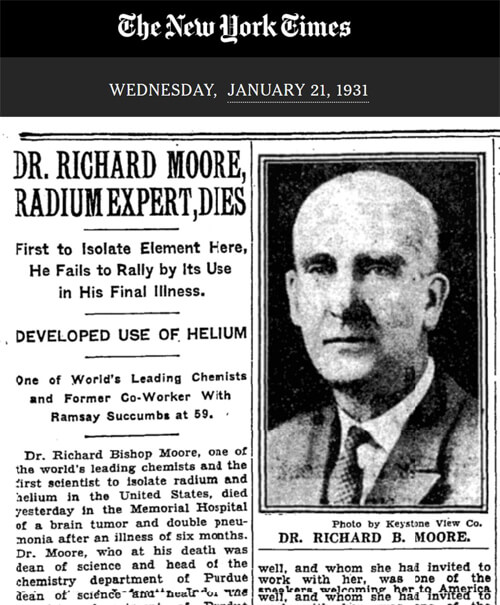

Soon after the United States entered the World War, Dr. Moore conceived the idea of substituting helium for the inflammable hydrogen in dirigibles and convinced the government of the feasibility of his plan. The war ended too soon for helium to be used by American airships, but Dr. Moore’s continued research in helium recovery from natural gas resulted in reducing the cost per cubic foot to ten cents while he was still in the Bureau of Mines and to the adoption of helium as the gas for all American airships. Richard B. Moore obituary, New York Times, January 21, 1931

In addition to his work with helium, Moore developed his own technique for extracting and producing radium at a plant in Denver, Colo. He also advocated the value of radium in cancer treatment, directing it to the attention of American physicians.

In 1926, Moore came to Purdue where he was named dean of the College of Science and Chemistry department head. He was instrumental in supporting the construction of a new chemistry building, saying: “We’ve got to build a big building. Chemistry is going to grow!” according to an oral history of M.G. Mellon.

The first phase of construction was completed in 1930. After a new addition doubled the size of the existing building in 1955, it was dedicated as the R.B. Wetherill Laboratory of Chemistry. It still stands on campus and was recognized as a National Historic Chemical Landmark by the American Chemical Society in 2013.

In 1931, a year after the new chemistry building was dedicated, Moore died in New York City of double pneumonia at the age of 59 after undergoing radium treatments for a brain tumor.

Additional sources:

Richard Moore obituary in New York Times, January 21, 1931

Helium, by Richard Moore, Bureau of Mines, June 1922

Eclipse information:

Purdue is hosting several solar eclipse viewing events on April 8, 2024. Read more about how to participate.