Students Explore the Human Side of Science in Purdue’s Nuclear Age Course

The nuclear age is often studied through equations, policies, and historical timelines. But for some Purdue students taking CHM 49000: The Nuclear Age: Its Science, History, and Ethics, the subject matter strikes closer to home.

The course is one of the Great Issues courses offered by the Purdue University College of Science and is taught by Jonathan Rienstra-Kiracofe, professor of practice for the James Tarpo Jr. and Margaret Tarpo Department of Chemistry. Last semester, he was taken aback by two students, Anna Klupshas and Dillon Kentaro Stahl, who shared that they have living relatives who had experienced some of the historical events taught in the class.

A Personal Connection Across Generations

For Purdue physics major Dillon Kentaro Stahl, the course was more than just an elective, it was a personal journey through his family’s history. A senior with a minor in astronomy, Stahl enrolled in the College of Science’s Great Issues course to deepen his understanding of how scientific discovery intersects with moral responsibility.

“The most important lesson I learned in CHM 49000 is the consideration of ethical and moral questions that go into any decision,” Stahl said. “This class taught me to analyze situations from a more three-dimensional perspective — to understand both sides before forming an opinion.”

That mindset took on special meaning when the course explored the development and consequences of nuclear weapons. Stahl’s family story is intertwined with atomic bombing of Hiroshima in 1945, one of history’s most devastating events.

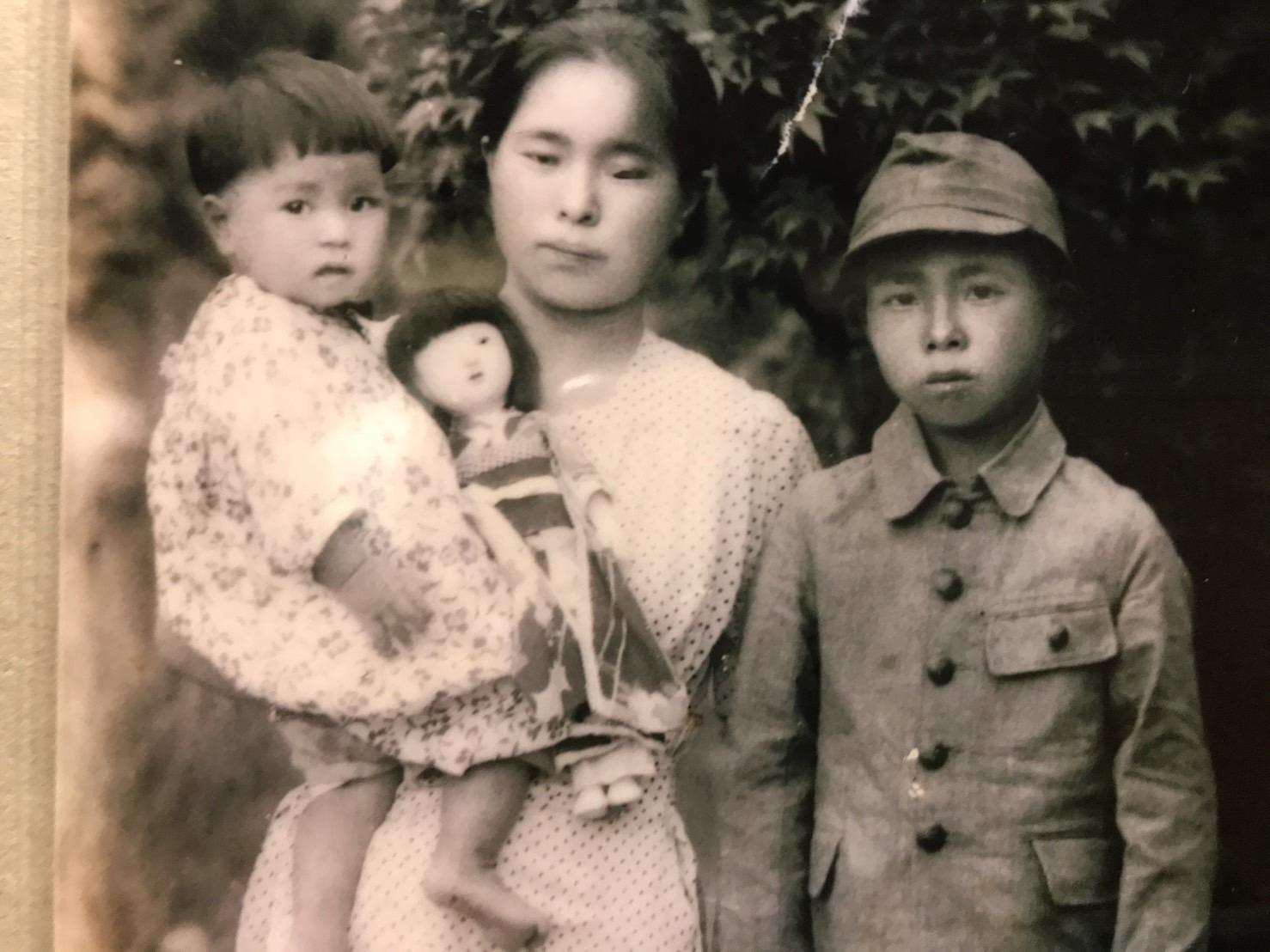

Pictured above is Stahl’s grandmother, great uncle, and great grandmother. Photo provided by Dillon Kentaro Stahl.

His grandmother, Ikuko, was just one year old when the bomb fell, and his great uncle, Hajime, was nine. Living in the countryside about 14 kilometers from the hypocenter, Hajime recalled being at school when he saw a blinding flash followed by the shockwave that shattered classroom windows. As he walked home, he saw the rising mushroom cloud and the “black rain” that fell over the city.

In the days that followed, Hajime, Ikuko, and their mother searched the ruins of Hiroshima for missing family members. They never found some of them, including an uncle and cousin who died instantly in the blast. Others, like Dillon’s great-grandparents, later succumbed to illnesses linked to radiation exposure. Despite the tragedy he witnessed, Hajime’s message to Dillon was not one of anger.

“He told me, shikata-ga-nai, which roughly translates nothing can be done about it,” Stahl said. “It is a concept of acceptance for something that cannot be changed. This is actually a common theme for many Hiroshima survivors that I have observed throughout my years.”

Another perspective of many Hiroshima survivors is echoed by the message his grandmother Ikuko still carries today:

“核戦争は絶対だめです。世界平和を祈る。”

Nuclear war is absolutely unacceptable. Pray for world peace.

Through the course and his family’s stories, Stahl said he’s learned that understanding history means seeing humanity on all sides and carrying those lessons forward.

“Taking into account my family history pertaining to Hiroshima, I was mainly only educated on the aftermath of the bombing of Hiroshima. I knew from a young age that the bombing was a horrific act and reflected the evils of war at the time,” he said. “However, upon taking CHM 49000, I was educated upon the status of Japan and the United States during the time of World War II, and the events leading up to both parties of the bombing. This has strictly changed my perspective on the event and through this I have learned a valuable lesson of having an open mind and trying to understand both sides of an issue. It requires one to be humble and put aside their beliefs to hear the other side of an argument. I think this is a truly important skill that everyone should possess whether in their professional career or personal life.”

A Legacy Marked by Chernobyl

For Anna Klupshas, a junior majoring in applied physics with minors in nuclear engineering and radiological health sciences, The Nuclear Age: Its Science, History, and Ethics offered more than a historical perspective, it offered understanding.

During the class, Klupshas and her classmates watched “Chernobyl Heart”, a documentary that examines the long-term health effects of the 1986 Chernobyl disaster. For Klupshas, the film struck a deeply personal chord. Her mother and grandmother were both directly affected by the fallout of that catastrophe.

Klupshas grandmother has few photos of her early days. Above is a photo of her as a young child in fourth grade in 1964. She is pictured at the far left in the second row and is wearing a dark colored school uniform. Photo provided by Anna Klupshas.

“My grandmother and mother are victims of Chernobyl,” Klupshas said. “My grandmother and mother are from Lithuania, an Eastern European country that was occupied by the Soviet Union from 1940 to 1991. During this period, Lithuania was under strict Soviet control. Both my mother and grandmother were required to learn Russian in school, wear red scarves symbolizing allegiance to the Bolsheviks, and wear Lenin pins on their uniforms. The Chernobyl disaster occurred in 1986, while Lithuania was still under Soviet rule. My grandmother, Laima Gaudi, remembers that the day of the explosion was bright and sunny.”

A bright, sunny morning that turned to a light rain, one that was unknowingly radioactive. The Soviet government remained silent for five days, only acknowledging the disaster after Sweden detected radioactive particles drifting west.

The family was instructed to add iodine to their milk in an attempt to block the absorption of radioactive iodine-131 to help prevent radiation-induced thyroid damage.

“My grandmother, who was working as a nurse at the time, recalls that the fourth floor of her hospital was reserved for Chernobyl survivors,” said Klupshas. “She visited it once and witnessed a woman giving birth to a deformed baby. After that, she never returned to the fourth floor.”

Back then, there was no Internet or social media. Information was passed by means of print, radio, or television. Gaudi said all information was locked, and the TV and radio were highly censored. People were isolated from any information.

Later, while traveling through Pryp’yat’, Ukraine, Gaudi saw a city turned ghost town. Trees were stripped bare in midsummer and soldiers were guarding the irradiated remains of homes.

“She recalls that many looters attempted to steal valuables from the evacuated area, but soldiers were under strict orders to shoot on sight, as nothing contaminated by radiation was allowed to be taken out,” said Klupshas. “Years later, when she and my mother immigrated to America, both experienced serious thyroid problems that required surgery. These issues are likely linked to radiation exposure from Chernobyl.”

Reflecting on the course, Klupshas said The Nuclear Age helped her see the historical significance and gravity of these topics. “I think that Great Issue classes are important and really helped me to understand the history behind the science I am interested in," she said. "Dr. R-K did a really good job teaching this course and it has definitely been one of my favorite classes I have taken."

A not-so-distant history

By blending science, history, and ethics, The Nuclear Age course helps students understand that the consequences of discovery still echo across generations. The past, as it turns out, is closer than we think.

About Purdue Chemistry

The Tarpo Department of Chemistry is internationally acclaimed for its excellence in chemical education and innovation, boasting two Nobel laureates in organic chemistry, the #1 ranked analytical chemistry program, and a highly successful drug discovery initiative that has generated hundreds of millions of dollars in royalties. chem.purdue.edu

Written by: Cheryl Pierce, Purdue College of Science

Contributors: Jonathan Rienstra-Kiracofe, Jonathan Rienstra-Kiracofe, professor of practice for the James Tarpo Jr. and Margaret Tarpo Department of Chemistry at Purdue University

Dillon Kentaro Stahl, undergraduate student

Anna Klupshas, undergraduate student